The Hendee Family Tree

Person Chart

Parents

| Father | Date of Birth | Mother | Date of Birth |

|---|---|---|---|

John Adams Sr. John Adams Sr. |

2/8/1691 |  Susannah Boylston Susannah Boylston |

3/5/1708 |

Partners

| Partner | Date of Birth | Children |

|---|---|---|

Abigail Smith Abigail Smith |

11/22/1744 |  Abigail Adams Abigail Adams President John Quincy Adams President John Quincy Adams Susanna Adams Susanna Adams Charles Adams Charles Adams Thomas Boylston Adams Thomas Boylston Adams Elizabeth Adams Elizabeth Adams |

Person Events

| Event Type | Date | Place | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

Birth Birth |

10/30/1735 | Braintree, Suffolk, Massachusetts Bay Colony, British Colonial America | |

Christening Christening |

11/6/1735 | Braintree, Suffolk, Massachusetts Bay Colony, British Colonial America | |

Marriage Marriage |

10/25/1764 | Weymouth, Suffolk, Massachusetts Bay Colony, British Colonial America | |

Place of Residence Place of Residence |

1810 | Braintree, Quincy, Norfolk, Massachusetts, United States | |

Place of Residence Place of Residence |

1820 | Quincy, Norfolk, Massachusetts, United States | |

Occupation Occupation |

Washington D.C., United States | President of the United States of America | |

Marriage Marriage |

|||

Death Death |

7/4/1826 | Quincy, Norfolk, Massachusetts, United States | |

Burial Burial |

7/10/1826 | Quincy, Norfolk, Massachusetts, United States |

Facts

| Fact | Description |

|---|---|

| National ID Number | 4180 |

Notes

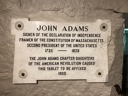

| 2nd United States President, first United States Vice President, Signer of the Declaration of Independence from Massachusetts, one of the Founding Fathers of the United States, and Revolutionary War Patriot. Born the first of two sons to John and Susanna Boylston Adams, he was born in Braintree, Massachusetts (now part of Quincy, MA), where his father was a Puritan farmer, a lieutenant in the militia, a town selectman (town councilman), and a descendant of the first settlers who had arrived in 1636 to found the town. John attended Harvard College, and after graduating in 1755, taught school in Worcester, Massachusetts for a few years. He decided that he wanted to become a lawyer, and studied law under James Putnam, a prominent lawyer in Worcester. In 1758, he was admitted to the Massachusetts Bar. A careful student, he would write detailed descriptions of events, court cases, and impressions of men, so that he could later study them and reflect upon them. His 1761 notes of the court argument of attorney James Otis on the legality of the Writs of Assistance has served to be one of the best historical records of that argument, helping historians to understand both that law, the public perceptions of the effects of that law, and the patriotism that existing in James Otis. With the Stamp Act of 1765, Adams rose to prominence as an opponent of the king, in which he argued to the Royal Governor that without representation in Parliament, Massachusetts had not assented to the Stamp Act. In 1770, following the Boston Massacre, the British soldiers involved were charged with murder. When no lawyer in Boston would agree to defend them, Adams argued on their behalf, and got six of them acquitted, with two soldiers who had fired directly into the crowd convicted only of manslaughter with dismissal from the Army. That same month, Adams was elected to the Massachusetts General Legislature, beginning his political career. Adams attended the First and Second Continental Congresses as a representative from Massachusetts. Believing in independence, he nominated George Washington of Virginia for Commander-in-Chief of the Continental Army. Tired of repeating his arguments for independence, Adams wrote a pamphlet "Thoughts on Government" (1776), which articulated his thoughts on independence and, more influentially, on the thought that monarchs, the aristocracy, and the common people all had to be mixed together and represented, in order to bring their support to the government. This thought was considered very radial at the time. "Thoughts on Government" was extremely influential on political thinkers, and was referenced as an authority in virtually every state when each wrote their state constitution. Adams would help write the Declaration of Independence, and would sign as a Massachusetts delegate. During the Revolution, he served as head of the Board of War and Ordnance, seeing that the Continental Army received the supplies it needed. In 1779, he wrote most of the Massachusetts Constitution, with help from his cousin, Sam Adams, and patriot James Bowdoin. During the Revolutionary War, Adams successfully negotiated treaties of recognition and friendship with France, Holland and Prussia, giving the United States its first foreign recognition as a nation. In 1785, he was appointed as the first Ambassador from the United States to Great Britain since the Revolution. When the Constitution of the United States was adopted, Adams ran for President, coming in second behind General George Washington. In accordance with the US Constitution, that made Washington President and Adams Vice President. As President of the Senate (the only duties that the Constitution gave the Vice President) he cast 29 tie-breaking votes, a record that still stands today. As the first Vice President, he set the standards for the sessions of the Congress, many of which are still enforced even today. In 1796, Adams ran for President on the Federalist Party platform against Governor Thomas Pinckney (Federalist), Thomas Jefferson (Democratic-Republican Party) and Senator Aaron Burr (also Democratic-Republican). In a narrow victory, Adams won the Presidency over the next candidate, Thomas Jefferson, thus, under the rules then in place, Jefferson become Adams' Vice President. In the next four years, President Adams built up the Navy, fought an undeclared war with France, and signed into law the Alien and Sedition Acts as an legal instrument against French actions in America (but was used by some politicians to silence their political opponents) and gave the first ever State of the Union address. In the election of 1800, each candidate ran for the first time with a vice presidential running mate. In this election, Jefferson teamed with Aaron Burr to defeat John Adams and his running mate, Charles Pinckney. Just before leaving the Presidency, Adams became the first US President to occupy the newly constructed White House, the official residence of the President. In his final days as President, Adams appointed his Secretary of State, John Marshall, as Chief Justice of the Supreme Court; Marshall would go on to establish much of the legal decisions that influence the Supreme Court even today, and he is considered one of the best Chief Justices the US ever had. Following his defeat, Adams retired into private life, returning to his farm in Massachusetts. He and Jefferson were bitter by the infighting of politics and would not speak to each other again until 1812, when Adams finally reconciled with Jefferson. Becoming friends again, the two men corresponded on a number of political and philosophical discussions, giving future historians deep insight into political thought of the times and of the two men. Sixteen months before his death, Adams' son, John Quincy Adams, became the sixth President of the United States, the first son of a President to achieve this office. On July 4, 1826, on the 50th Anniversary of the Declaration of Independence, Adams died at his home in Quincy. His last words were "Jefferson lives," considered a tribute of his deep affection for his friend and former rival. However, Thomas Jefferson had died a few hours earlier than his friend, John Adams, that same day. |

| Family of John Adams John Adams was born on 19 October 1735 (Julian Calendar) /30 October 1735 (Modern Calendar) in Braintree, Norfolk, Massachusetts [1] (now Quincy, Massachusetts) to the Puritan deacon John Adams and Susannah Boylston, [2] the daughter of a prominent family. While his father's name was John Adams Sr., the younger John Adams has never been referred to as John Adams Jr.[3] Adams married in 1764 to 20-year-old Abigail Quincy Smith in Weymouth.[4] They had five children in ten years, and one more, a stillborn daughter, in 1777. Their first son, John Quincy Adams, would become the sixth president of the United States.[3] [2][5] Adams' great-great grandfather, Henry Adams, emigrated circa 1636 from Braintree, England to the Massachusetts Bay Colony. Henry's 89 grandchildren earned him the modern nickname of "Founder of New England." In terms of contemporaries, John Adams was second cousin to the statesman and colonial leader Samuel Adams. Adams was highly conscious of his heritage. He considered his Puritan ancestors "bearers of freedom." He also inherited a seal with the Boylston arms on it from his mother. This he loved and used frequently until his presidency, when he thought that the use of heraldry might remind the American public of monarchies. Career of John Adams As a young man, Adams attended Harvard College. His father expected him to become a minister. Instead, Adams graduated in 1755, taught for three years, and then began to study law under James Putnam. He had a talent for interpreting law and for recording observations of the court in action. He became prominently involved in politics in 1765 as an opponent of the Stamp Act. In 1770, he won election to legislative office in the Massachusetts General Court. He later served as a Massachusetts representative to the First (1774) and the Second (1775-1778) Continental Congresses, as ambassador to Great Britain (1785-1788) and to the Netherlands (1782-1788), and as Vice President under George Washington from 1789 to 1797. Adams found the role of Vice President to be frustrating. He wrote to wife Abigail that, "My country has in its wisdom contrived for me the most insignificant office that ever the invention of man contrived or his imagination conceived." After George Washington stepped down, Americans narrowly elected John Adams, a Federalist, President over his Democratic-Republican opponent, Thomas Jefferson. Jefferson became Adams's Vice President. In 1800, Jefferson finally won the presidential vote, and Adams retired to private life in 1801 when his term of office expired.... Retirement & Death President John Adams retired to his farm in Quincy, Massachusetts. Here he penned his elaborate letters to Thomas Jefferson. Here on 04 July 1826, he whispered his last words: “Thomas Jefferson survives.” But Jefferson had died at Monticello a few hours earlier.[6] In 1820, he voted as elector of president and vice president; and, in the same year, at the advanced age of 85, he was a member of the convention of Massachusetts, assembled to revise the constitution of that commonwealth. Mr. Adams retained the faculties of his mind, in remarkable perfection, to the end of his long life. His unabated love of reading and contemplation, added to an interesting circle of friendship and affection, were sources of felicity in declining years, which seldom fall to lot of any one.[7] On 04 July 1826, the fiftieth anniversary of the adoption of the Declaration of Independence, Adams died at his home in Quincy, Massachusetts. Told that it was the Fourth, he answered clearly, "It is a great day. It is a good day." His last words have been reported as "Thomas Jefferson survives". His death left Charles Carroll of Carrollton as the last surviving signatory of the Declaration of Independence. John Adams died while his son John Quincy Adams was president.[8] "He saw around him that prosperity and general happiness, which had been the object of his public cares and labours. No man ever beheld more clearly, and for a longer time, the great and beneficial effects of the services rendered by himself to his country. That liberty, which he so early defended, that independence, of which he was so able an advocate and supporter, he saw, we trust, firmly and securely established. The population of the country thickened around him faster, and extended wider, than his own sanguine predictions had anticipated; and the wealth, respectability, and power of the nation, sprang up to a magnitude, which it is quite impossible he could have expected to witness, in his day. He lived, also, to behold those principles of civil freedom, which had been developed, established, and practically applied in America, attract attention, command respect, and awaken imitation, in other regions of the globe; and well might, and well did he exclaim, 'where will the consequences of the American revolution end!' "If any thing yet remains to fill this cup of happiness, let it be added, that he lived to see a great and intelligent people bestow the highest honor in their gift, where he had bestowed his own kindest parental affections, and lodged his fondest hopes. "At length the day approached when this eminent patriot was to be summoned to another world; and, as if to render that day forever memorable in the annals of American history, it was the day on which the illustrious Jefferson was himself, also to terminate his distinguished earthly career. That day was the fiftieth anniversary of the Declaration of Independence. "Until within a few days previous, Mr. Adams had exhibited no indications of rapid decline. The morning of the fourth of July, 1826, he was unable to rise from his bed. Neither to himself, or his friends, however, was his dissolution supposed to be so near. He was asked to suggest a toast, appropriate to the celebration of the day. His mind seemed to glance back to the hour in which, fifty years before, he had voted for the Declaration of Independence, and with the spirit with which he then raised his hand, he now exclaimed, 'Independence forever.' At four o'clock in the afternoon he expired. Mr. Jefferson had departed a few hours before him." -- Daniel Webster in section "Retirement and Death". p9, John Vinci, "Biography of John Adams," "They, (Mr. Adams and Mr. Jefferson,) departed cheered by the benediction of their country, to whom they left the inheritance of their fame, and the memory of their bright example. If we turn our thoughts to the condition of their country, in the contrast of the first and last day of that half century, how resplendent and sublime is the transition from gloom to glory! Then, glancing through the same lapse of time, in the condition of the individuals, we see the first day marked with fulness (sic) of vigor of youth, in the pledge of their lives, their fortunes and their sacred honor, to the cause of freedom and of mankind. And on the last, extended on the bed of death, with but sense and sensibility left to breathe a last aspiration to heaven of blessing upon their country; may we not humbly hope, that to them, too, it was a pledge of transition from gloom to glory; and that while their mortal vestments were sinking into the clod of the valley, their emancipated spirits were ascending to the bosom of their God!" -- son John Quincy Adams.[7] His crypt lies at United First Parish Church (also known as the Church of the Presidents) in Quincy, Massachusetts. Originally, he was buried in Hancock Cemetery, across the road from the Church. |